Contents

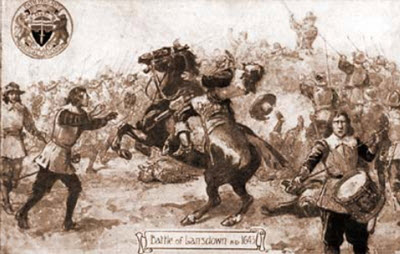

The Battle of Lansdowne was fought on 5 July 1643 between Parliamentarian and Royalist forces in the English Civil War. Lansdowne, sometimes spelled Lansdown, is located near Bath in Somerset.

The battle was won by the Royalists under Lord Hopton, forcing the Sir William Waller led Parliamentarians to retreat from their hilltop position. The Royalists, however, suffered such a great number of casualties that they themselves were required to retire. The Battle of Lansdowne was considered a pyrrhic victory for the royalist side.

The site of the battle is marked by a monument erected in 1720 to commemorate royalist Sir Bevil Greenville, commander of the Cornish pikemen. He was fatally injured in the fight and died at the Cold Ashton Rectory. Coordinates for the monument: 51°25′53″N 2°23′58″W.

Short facts about the Battle of Lansdowne

| Location | Lansdowne Hill, near Bath, England |

| Date | 5 July, 1643 |

| Belligerents | Parliamentarians

Royalists |

| Result | Royalist victory |

| Parliamentarians | Royalists | |

| Commanders and leaders | Sir William Waller | Lord Hopton, lieutenant-general

Sir Bevil Grenville, commander of the Cornish pikemen Colonel John Giffard of Brightley, commander of the Devon pikemen |

| Strength |

2,500 horse |

2,000 horse |

| Casualties and Losses | 20 killed

60 wounded |

200 – 300 killed

600 – 700 wounded |

Prelude

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of three wars between Parliamentarians (“Roundheads”) and Royalists (“Cavaliers”). The first of these wars was fought in 1642-1646, between the supporters of King Charles I and the supporters of the Long Parliament.

By late May 1643, a royalist army led by Lord Hopton had captured most of south-western England, and was marching eastward toward a region held by Parliamentarian forces. With the aim of obstructing further advances by the Royalists, Sir William Waller’s Parliamentarian army was present Bath.

By late May 1643, a royalist army led by Lord Hopton had captured most of south-western England, and was marching eastward toward a region held by Parliamentarian forces. With the aim of obstructing further advances by the Royalists, Sir William Waller’s Parliamentarian army was present Bath.

On 2 July, the Royalists took control over a bridge in Bradford on Avon, a village located in the western part of Wiltshire, not far from the Somerset border. The following day, skirmishes occurred at Claverton and at Waller’s positions south and east of Bath. As the main Royalist force moved north through Batheaston to Marshfield, Waller’s forces retired to a Lansdowne Hill – an elevated position that they deemed would be easier to defend.

When Hopton’s forces reached Lansdowne Hill on 4 July, they came to the same conclusion; the hill was a strong position. Hopton’s forces withdrew approximately 8 kilometres to Marshfield, pursued by Waller’s cavalry.

The Battle of Lansdowne

Early on 5 July, Waller’s men built crude breastworks for the infantry at the northern end of the hill. his. Waller also gave some of his cavalry order to seek out Hopton’s outposts, and they successfully chased away the disorganised Royalist cavalry. The noise and commotion caused the Royalist army to form up and move west until they could see Waller’s forces.

The following two hours were marked by tentative skirmishes, and Hopton trying to withdraw back again. Waller ordered men on horseback to attack Hopton’s rearguard. The Parliamentarian cavalry routed the Royalist cavalry, but the Royalist infantry stood firm.

Now, Hopton’s army turned about and confused and disorganised fighting with Waller’s cavalry commenced. When the Royalists finally defeated the Parliamentarian cavalry, Hopton’s Cornish foot regiments had already began to advance towards Lansdowne Hill without being ordered to.

Hopton gave order to attack Lansdowne Hill and his army charged up the steep slopes of the hill. Waller’s army was considerably smaller but had an advantageous position and caused great damage to Hopton’s cavalry. A large number of Royalists died or were severely injured, and many panicked. Roughly 1,400 members of the Royalist force fled, some of them making it all the way to Oxford.

Hopton gave order to attack Lansdowne Hill and his army charged up the steep slopes of the hill. Waller’s army was considerably smaller but had an advantageous position and caused great damage to Hopton’s cavalry. A large number of Royalists died or were severely injured, and many panicked. Roughly 1,400 members of the Royalist force fled, some of them making it all the way to Oxford.

Hopton’s Cornish pikemen, led by Sir Bevil Grenville, successfully stormed Waller’s improvised breastworks while Hopton’s musketeers outflanked Waller through the woods. A Parliamentarian counter-attack by men on horses forced Grenville into hand-to-hand combat where he was fatally injured.

Waller’s infantry fell back to a wall that ran across the crest of the hill. From this position, they defended themselves with muskets until sunset. When it got dark enough, they placed burning matches on the wall to make it look as if they were still there, while quietly withdrawing from the area.

The Royalist had won the Battle of Lansdowne, but at a great cost.

Aftermath

The Royalist army had not just lost a lot of manpower; they were also short on horses and ammunition. On 6 July, Hopton was injured and temporarily blinded when a Royalist ammunition cart exploded.

Depleted, Hopton’s forces retired to Devizes. They were in such poor condition that Waller actually offered Hopton hospitality in Bath, to where Waller and his force had retired. (Waller and Hopton were old friends.) Hopton refused the invitation.

In Bath, Waller had received reinforcements and was ready to attack the Royalist forces, but since they withdrew the plans were changed.